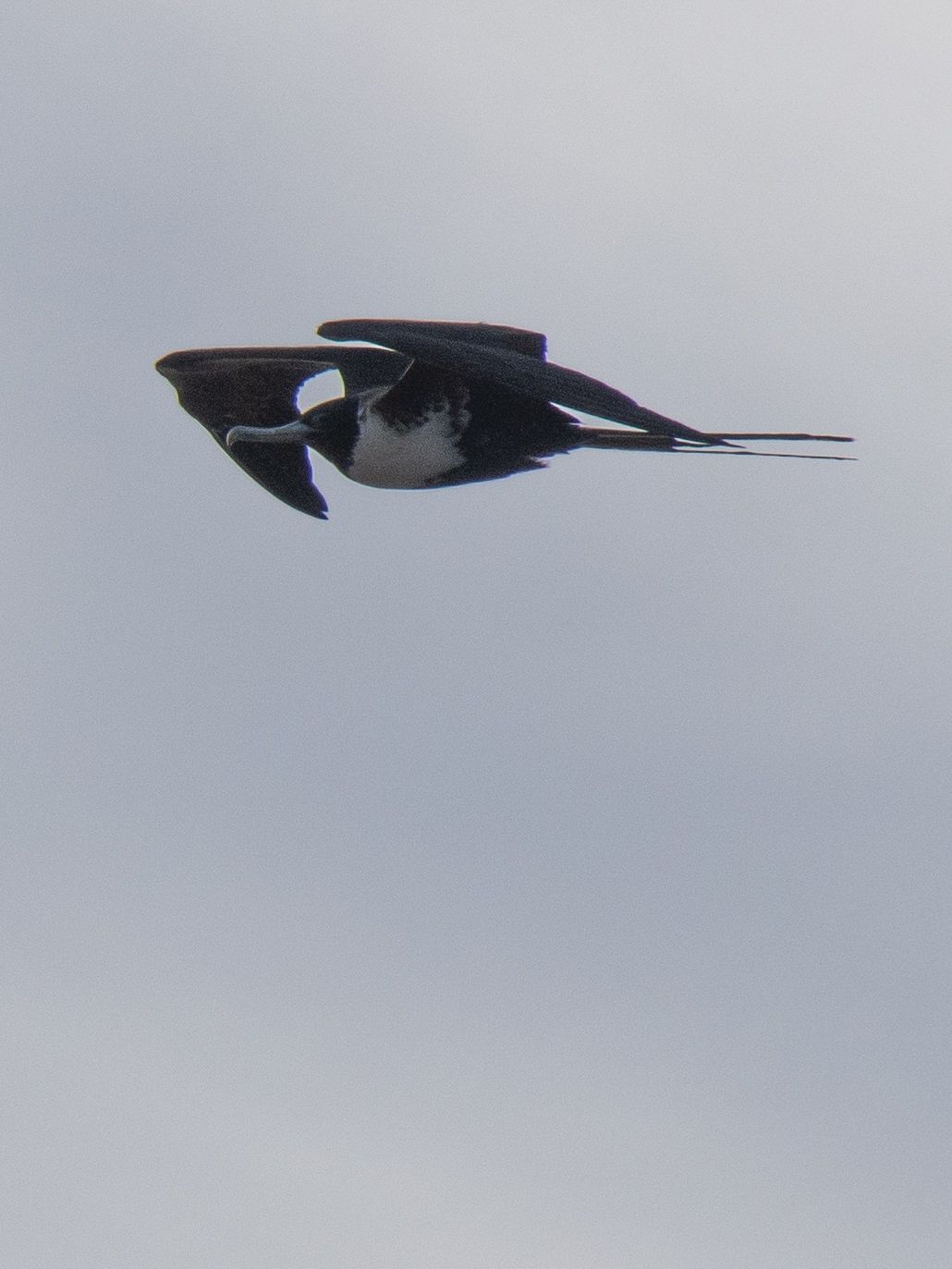

Aside from my beloved X.O., Magnificent Frigatebirds have been my most constant companions while exploring Mexican waters aboard Rejoice. I found them breathtaking from the start, appearing in their in elegant soaring congregations hundreds of feet above us, welcoming us to the waters of Pacific Mexico as we made our way around Cabo San Lucas.

My fascination and respect only grew as I learned more about this singular species. The frigatebird's wingspan can be as wide as seven and a half feet, giving it the highest ratio of wing surface to body weight of any bird. Recent research published in Science revealed the extraordinary lives these bodies make possible.

Frigatebirds stay aloft for weeks at a time, soaring up to 12,000 feet in the air, which is higher than any other bird has been observed to fly. According to ornithologist Henri Weimerskirch, they use very little energy when they fly by doing something no other bird is known to do: flying intentionally into clouds. They ride the updraft to the top of a cumulus cloud, and once there, can soar for up to two months, covering more than 300 miles a day. Weimerskirch observed one frigate soar over 40 miles without beating its wings.

Imagine soaring almost motionless, 4000 feet in the air, for three hours at a time, well out of sight of land.

Over cocktails with our dear friends on Migration, I was enthusiastically sharing what I had learned, and Alene asked the obvious question that had failed to occurred to me. "How do they sleep?" Niels Rattenborg answers in Nature that they don't sleep much. By embedding EEGs into the brains of 15 frigatebirds, Rattenborg learned that less than 3% of their flight time is spent sleeping, even on passages as long as 10 days. They sleep in short ten second bursts, and often sleep with only one hemisphere of their brain. They make up for it on land, sleeping more than 12 hours a day. Most astonishingly, frigatebird foraging and flight performance doesn't appear to be negatively impacted by so little sleep. Rattenborg's 2016 study was the first to prove the long held belief that long flight birds can sleep on the wing.

There's a good reason why these impressive feats are mundane for frigatebirds: their feathers aren't waterproof. Other seabirds have highly developed uropygial glands, which produce a waxy substance called preen oil, which they rub into their feathers with their beaks. Frigatebirds have tiny uropygial glands, which leaves their feathers so unprotected that they never intentionally land on water.

They can't dive for food either, instead they skim fast over the water, using their hooked beaks to catch squid swimming close to the surface or flying fish taking to the air to escape predatory tuna. There's always some risk of drowning, especially when seas are choppy. Perhaps this is what drives the frigatebird to kleptoparasitism. They pirate food from other seabirds, like red-billed tropicbirds and blue-footed boobies. They're brutal about it too, capturing the other bird in mid-flight, holding them upside down by the legs, and shaking them until they disgorge their catch. Then they release their poor victim, dive, and catch the purloined morsel before it is lost to the sea.

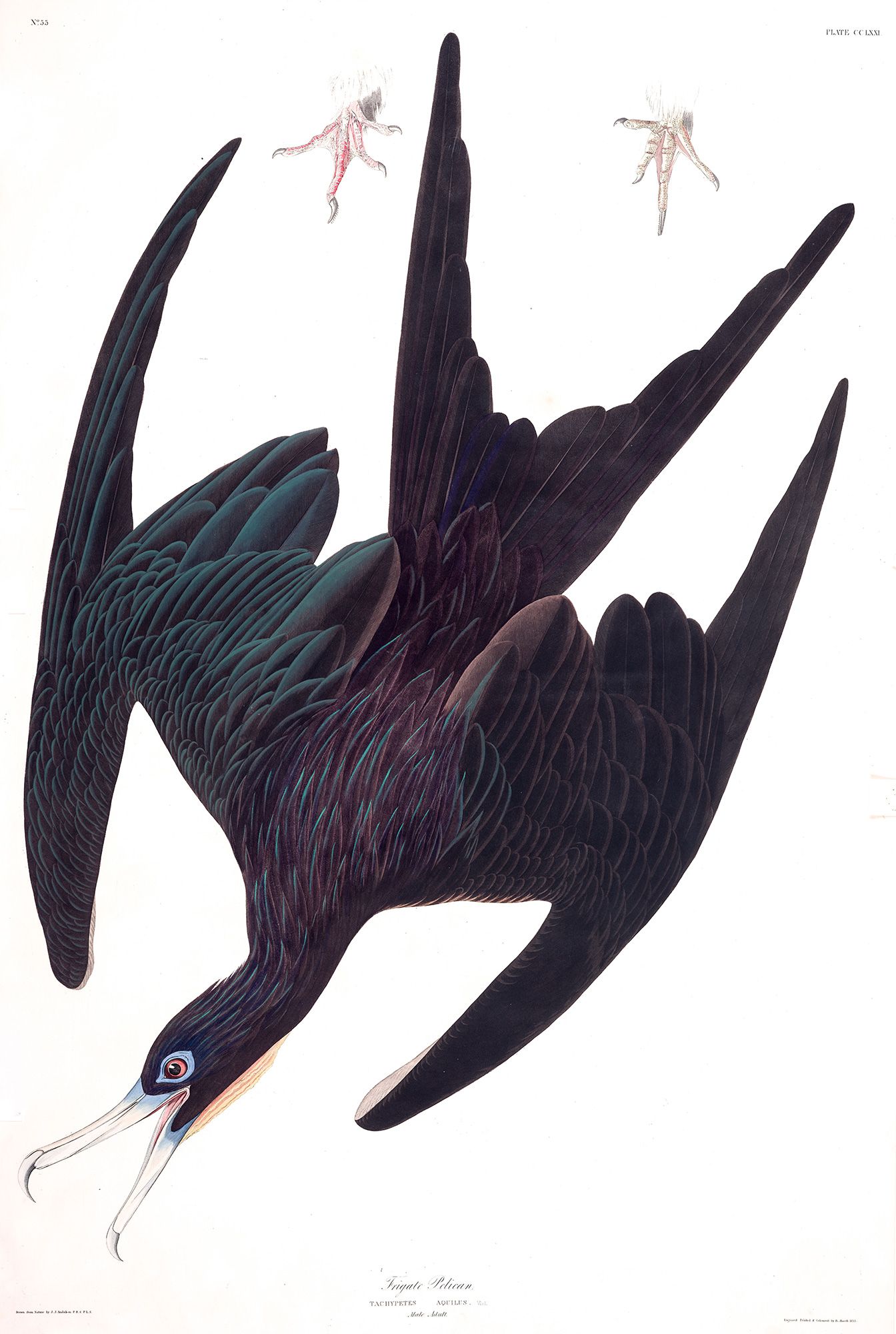

John J. Audubon's 1827 account of the frigatebird's dining habits is hard to improve on:

The bird of which I speak comes from on high with the velocity of a meteor, and on nearing the object of its pursuit, which its keen eye has spied while fishing at a distance, darts on either side to cut off all retreat, and with open bill forces it to drop or disgorge the fish which it has just caught. See him now! Yonder, over the waves leaps the brilliant dolphin, as he pursues the flying-fishes, which he expects to seize the moment they drop into the water. The Frigate-bird, who has marked them, closes his wings, dives toward them, and now ascending, holds one of the tiny things across his bill. Already fifty yards above the sea, he spies a porpoise in full chase, launches towards the spot, and in passing seizes the mullet that had escaped from its dreaded foe; but now, having obtained a fish too large for his gullet, he rises, munching it all the while, as if bound for the skies. Three or four of his own tribe have watched him and observed his success. They shoot towards him on broadly extended pinions, rise in wide circles, smoothly, yet as swiftly as himself. They are now all at the same height, and each as it overtakes him, lashes him with its wings, and tugs at his prey. See! one has fairly robbed him, but before he can secure the contested fish it drops. One of the other birds has caught it, but he is pursued by all. From bill to bill, and through the air, rapidly falls the fish, until it drops quite dead on the waters, and sinks into the deep.

Frigatebirds nest in colonies. We visited the colony on Isla Isabel in Mexico's Gulf of California, where we discovered just how differently frigatebirds behave at home. Frigatebirds nest very close together. Unlike other seabirds, it's easy to tell male and female frigatebirds apart. Males have iridescent black plumage and a distinctive red gular sack at the throat. Females are larger than males, have duller black plumage, and prominent white chests.

Their courtship ritual begins when a group of males gather, inflate their gular sacks like enormous scarlet balloons, clack their bills, and wave their wings to attract passing females.

Once paired, males will gather nest materials for the female to build with. Both will incubate the one white egg for almost two months. Nests are never left unguarded, as neighboring frigatebirds won't hesitate to devour eggs and even young. Because of their unusual physiology, young frigatebirds are dependent on their parents longer than any other bird species. Seasonally monogamous males participate equally in care and feeding for about three months before abandoning the nest to return to sea.

Young will first take flight at six months, and females will continue taking care of fledglings, often for more than a year.

Due to the frigatebird's poorly developed legs, flight failures are often fatal.

There is a fish camp and a couple of research camps on Isla Isabel, but there's no mistaking who the island belongs to. I have always felt at home in wild places, but being somewhere with a complex environmental culture that had so little to do with human beings gave me a feeling of communion with these creatures that I hold on to today. Much of our voyage has centered on rediscovering the wildness inside of us, but Isla Isabel is where it really unfolded for me.

Several sailors who have been cruising longer than I have insist that once I've had to clean Rejoice's decks of one of their voluminous shits, or climb to the top of the mast to repair the sensitive wind instruments that invariably become their favorite perch, I'll come to loathe these extraordinary creatures as much as they do, but I do not believe them. I have such admiration for these creatures of extremes, these seabirds who can't touch the sea, these careful homemakers who leave their nests to soar for weeks on end in radiant stillness in the sky.